A timeline of the emergence of the mpMRI in prostate cancer diagnosis

One of the key underlying messages coming out of this month’s long-awaited post-pandemic Congress of the European Association of Urology was the almost universal acceptance of the role of specialist MRI scans in prostate cancer diagnosis and its continued growth in adoption and implementation worldwide. Debate on its value and role has now shifted to how to improve its efficacy and accuracy, with a particular focus on PET/MRI.

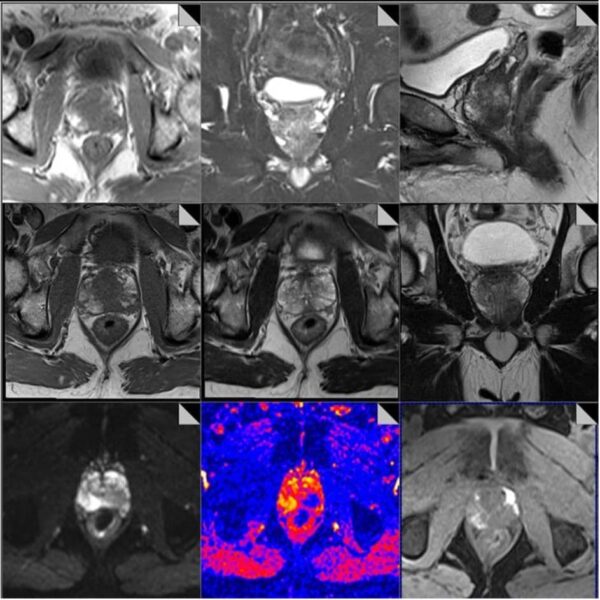

We’ve come a long way since the design of the PROMIS trial, launched in 2012 and published in 2017. It set the stage for a significant paradigm shift in prostate cancer diagnostics using specialist MRI scans,

testing the value of Multi Parametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) for men with a suspicion of prostate cancer who had been recommended to have a prostate biopsy. It investigated whether MRI could be used (i) to advise whether or not men might safely avoid biopsy and (ii) to improve biopsies for men who have them.

PROMIS demonstrated the following:

- TRUS post PSA blood test results is a poor test for the diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer. The sensitivity was only 48% and thus missed over half the cases.

- Specialist MRI scans performed after the PSA blood test provide a highly sensitive test (93%) for the detection of clinically significant cancer and if performed prior to the biopsy, can identify about 25% of men who might safely avoid a biopsy.

- Performing an MRI scan prior to biopsy was highly cost effective.

Approval from NICE came in 2018, with guidance recommending that “all men with suspected prostate cancer should be offered a specialist MRI scan when they’re referred to the hospital in England, before a biopsy.”

While this was welcomed overall, it also prompted some concern about the scale of the task to implement MRI for prostate cancer across the country, and the readiness of the NHS to achieve this. In 2019 Dr Philip Haslam, mpMRI lead at the Royal College of Radiologists, suggested that the introduction of MRI would increase radiologists’ workloads quite a bit over the next few years. “We’ve only got a finite number of trained radiologists in the UK and a finite number of scanners that everyone is fighting to use, who says prostate cancer gets priority?” he asked.

In spite of these concerns – which are still present – access to MRI for prostate cancer diagnosis has been building across the NHS. While Prostate Cancer UK expressed concern that 2018 only 57% of hospitals provided the specialist scans for prostate cancer patients, by 2022 this had increased to 82% of hospitals.

What we’re most concerned about now is on the standards of imaging and radiology reporting that informs the diagnosing clinician in his/her diagnosis. It goes without saying that a high-quality MRI scan and report is absolutely essential to focal therapy. Put bluntly, you can’t treat what you can’t see. Some would add also that if you can see it, you should treat it. Whatever the perspective, confidence in the presence, location, size and severity of lesions on the prostate is essential to assessing a patient’s suitability for focal therapy and to the success of his subsequent treatment.

We often see patients whose MRI scan and, more often, its reporting is inadequate to make an accurate and safe assessment for focal therapy. It appears for some men the success of scaling up access to specialist MRI scans for the prostate has come at a cost in quality and variability.

We see variability in scanners, radiographic expertise in imaging and, crucially, radiological expertise in reporting on individual patient scans.

Dr Clare Allen, consultant radiologist at UCLH and the Focal Therapy Clinic, has led a study investigating an approach to standardise prostate MRI practice across a group of London hospitals. It explored prostate specialist MRI protocols across 14 London hospitals, seeking to determine whether standardisation improves diagnostic quality. Its conclusions were clear: “targeted intervention at a regional level can improve the diagnostic quality of specialist prostate MRI protocols, with implications for improving prostate cancer detection rates and targeted biopsies”.

We strongly believe that bringing imaging and reporting standards in line across hospitals would benefit so many men, improving their diagnoses and giving them options for treatment.

Two additional developments may eventually impact the variability in quality and access that we see with prostate imaging.

Rapid MRI screening is being developed at Imperial College London, which would give large numbers of men access to imaging at a standard sufficient to make decisions on further diagnostics. “Prostagram” is being developed as a mass screening protocol, similar to how mammograms are used to screen for breast cancer.

Artifical Intelligence (AI) tools for reading and interpreting specialist MRI scans of the prostate are also in development. Most of these are designed to enhance the role of the radiologist rather than replace it, and show promise in lesion detection, volume estimation and characterisation.

Do you have questions about the role of mpMRI in prostate cancer diagnostics? Or an experience to share? We’d love to hear from you